The irrepressible monkey in the machine

Neither "AI" nor TikTok (nor Facebook nor NBC nor...) can "hack" human beings.

The brilliant game designer

wrote a wonderful post about why he’s not afraid of one particular vision of an AI dystopia, which he encountered in the work of David Chapman. This vision is one in which AI makes content so compelling we become enslaved to it, addicted to it, unable to turn away from it. This is not a new concept, as Lantz notes when he compares it to “the show in [Infinite Jest] or the joke so funny it kills from the Monty Python bit,” but, proponents might argue, it’s freshly plausible given AI’s capacity to e.g. endlessly and competently generate personalized VR pornography with mobile gaming characteristics (or whatever).I highly recommend reading his entire essay, as his thoughts in rebuttal to this fear touch on so many points of interest that I can’t possibly excerpt even a representative sample. Setting aside profound reflections on how e.g. “art has [an] adversarial relationship between the audience and the artist… it’s an arms race between entrancement and boredom,” I wanted to focus on a particular aside:

“[The idea] of an irresistibly addictive media property reminds me of the calls I sometimes receive from journalists who want to talk about how game developers hire psychology researchers to maximize the compulsive stickiness of their games by manipulating the primal logic of our brains’ deep behavioral circuits. My answer always goes something like this - yes, it’s true that some companies do this, but it’s not that important or scary. “Staff Psychologist” at Tencent or Supercell or wherever is probably mostly a bullshit job, there to look fancy and impressive, not to provide a killer marketplace advantage.”

I think many of us who’ve been inside these sorts of enterprises desperately wish we could convey to outsiders just how little capacity to hack or influence or control human populations they in fact have. When I worked at Facebook, it was popular to assert that we had “figured out how to make addictive products,” that we used “an understanding of the dopamine system” (or whatever other faddish synecdoche for “the human mind” was in vogue at the time) that allowed us to hijack human volition, and even that we “controlled” “how people felt” or “what they thought.”

From within Facebook, I could see quite clearly that none of this was true. We didn’t need an “understanding of dopamine” to know that people responded to notifications about people liking their selfies; our ranking systems embodied no knowledge or goals beyond “show them stuff they like,” as measured in view time, clicks or taps, visits, etc. We couldn’t control —or even seemingly influence— what people thought in the area that mattered most to us: what they thought about Facebook. (Lots of them fucking hated us and we were powerless to change that). And our army of researchers, many academic psychologists, produced white papers few read in which they carefully demonstrated such insights as “people are more responsive to photos of people they know than to photos of strangers” and so on. In sum:

there was no psychological or neurophysiological theorizing of any relevance or import to product development, and there didn’t need to be;

we couldn’t control or influence the things we most wanted to, let alone e.g. “what Americans thought of elections” or whatever;

we were regularly shocked by new products on the market achieving success with our users, something you’d think masters of understanding in total control of their users wouldn’t experience much;

almost every sinister explanation for something we shipped was a borderline-flattering fantasy quite removed from a prosaic, straightforward reality.

It was like reading a Yelp review of a local mom-and-pop diner:

“Their advanced psychometric engineering division has no doubt determined that the satiation of hunger is one of the most intensely-sought states humans pursue, and the subtle colocation of that satiation with their business establishes in the mind of hordes of programmable automata that “Mom and Pop Diner” means satiation. Even customers who might want not to eat at the diner find themselves drawn in, helplessly, by their conditioning; tests indicate that regular patrons even grow hungrier when they enter the premises. Their menu is practically a mind-control device, in which options are described in hyperbolically tantalizing terms (and in which prices are displayed in a smaller font), preventing customers from fully understanding the context for their decisions as their urges overwhelm them and they order, once again, a burger.”

Yes, it’s all quite dark, what mom and pop and every other business is up to! Inside companies I’ve worked at, the only way to describe the relationship to users and customers is to say it was fearful. Companies are desperate to appeal to the market; companies are terrified of their users, whom they do not really understand. One of the better observations Steve Jobs made is in this vein:

“When you’re young, you look at television and think, There’s a conspiracy. The networks have conspired to dumb us down. But when you get a little older, you realize that’s not true. The networks are in business to give people exactly what they want. That’s a far more depressing thought. Conspiracy is optimistic! You can shoot the bastards! We can have a revolution! But the networks are really in business to give people what they want. It’s the truth.”

For my entire life, there have been memes that this or that technology or company has cracked the code to subverting human will, shaping our minds into various kinds of “false consciousness,” misleading us about what we want, and so on. Such theories sound absurd in retrospect; who today could imagine that NBC, CBS, and ABC controlled what people thought? If they did, how did they get more-or-less annihilated when the Internet arrived? Why didn’t they simply influence Americans to dislike the Internet and to prefer television? (Because they never controlled what Americans thought! They were powerless before their “users”!).

The team I worked on at Facebook was the one charged with beating back Snapchat, as it was then called; it was considered strategically vital. Our purpose was to increase the amount of personal, original content that people posted. Again, many thought we were able to influence electoral outcomes, and in some cases, even more fundamental phenomena, like “people’s beliefs” or “how we think about the world.” Yet there we were, presenting lame-ass designs to Zuck showing bigger composers, better post type variety, other ridiculous and pathetic ideas. Facebook, which many at the time said had “far too much power” to control discourse and warp reality, couldn’t persuade its users to post to Facebook. And in all the conversations I had about this problem, I don’t remember anyone getting into “the science of human addiction” or anything of the sort. We did very ordinary research (for example: asking users why they weren’t posting); we built very ordinary features to try and help; and ultimately, what worked was just copying Snapchat anyway.

I am very confident this is true of TikTok today. TikTok is an amazing product because of its format and its ranking (and how they relate). There are possibly “experts on psychology” in their buildings, writing long emails no one reads, but TikTok doesn’t know the first thing about “how to control people” or “who you are at a deep level” or “the ways to exploit the limbic system” or anything else along those lines; what they have is: vast and fresh inventory and incredible ranking, especially their explore / exploit balance. TikTok executives cannot predict what their children or spouses will do, let alone what you or the rest of the American people will do. They control and understand far less than people suspect.

The rest of Lantz’s post is more interesting than these remarks, by far, and he goes into hilarious and concrete detail about the actual impact of psychological theories in the development of software; but the preponderance of agency-denying, human-reducing theories of these sorts is so great that I can’t pass up an opportunity to push back on one. The fact that humans make choices you disagree with —or even self-destructive choices!— is not proof that they have been hypnotized or hacked. There is no hacking humans, not for long anyway; and this is a very important thing to understand for a wide range of questions, from public policy to AI.

At a general level: the human mind is relentlessly restless and adaptive; and although this is painful for the individual, it is very good for society. Lantz describes this in terms of adversariality:

It is this adversarial dynamic that is missing from Chapman’s picture of a world hopelessly outfoxed by stats-driven recommendation algorithms. Cultural works aren’t hedonic appliances dispensing experiences with greater and greater efficiency for audiences to passively consume. Creators and audiences are always engaged in an active process of outmaneuvering each other.

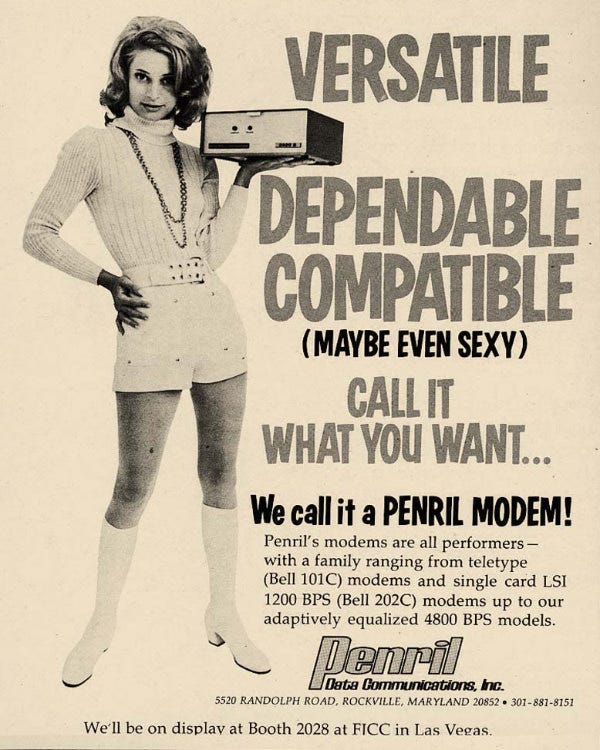

This competitive dynamic is omnipresent. Even if some Ph.D figured out “how humans work” in some sense that enabled a company to exploit it, humans would very quickly incorporate this implicit or explicit knowledge into their thinking and the hack would stop working.1 There may have been some moment in time when academics helped advertisers create commercials that made use of deep human desires and lots of humans fell for e.g. an attractive person posed alongside an unrelated product; there rapidly followed widespread understanding that “ads are trying to make use of deep human desires,” then cynicism about “ads as such,” to the extent that today most humans strain to imagine how anyone could be persuaded by a clumsy attempt such as the following:

Thus Lantz’s arm’s race: audiences get savvier, advertisers try new approaches, and because the human mind is capable of universality, this will never end. Today, while “sex [still] sells,” a larger percentage of commercials flatter the moral status of potential consumers, or appeal to their sense of virtue in whatever subtle ways, or tell a story of “lifestyles,” our primary intact way of reasoning about “what is good in life.” The point is merely that there is no permanent hack to be found in any of these fields, or in the academic work they ostensibly make use of. Humans adapt, change, shift, and remain just outrageously hard to influence, let alone “control,” and this cannot change, no matter how expert the efforts at manipulation are.

Lantz concludes:

Humans are not helpless creatures who must be protected from the grindhouse of optimized infotainment. We are a race of attention warriors, created by the universe in order that it might observe itself. Now the universe has slapped us across the face, and we have the taste of our own blood in our mouths, but we must not look away. The poet must not avert his eyes.

Indeed, there’s no reason to look away anyway: you can rest assured that whatever kaleidoscope of stimulation (or even intoxication) AI conjures, you will get bored of it; getting bored is what we do, and it turns out to be a rather profound feature of our consciousness (and thank goodness, because Lordy do I get bored a lot). In any event, I cannot recommend his Substack enough!

This came up in last week’s post: “…worse: any humans who learn “how human populations behave” are liable to behave differently once they’ve factored in that knowledge! This is worse because while the former is imaginably surmountable —someday, we will be able to model the mind completely, unless we grant some form of dualism— this is not. Humans don’t stop adapting, including to new knowledge about how humans adapt.”

Formidable attention warriors like you don’t get hacked. That’s why you *love* the bold taste of Marlborough

Good piece, but I can't help feel as though you've built a bit of a false dichotomy here.

I fully agree that it's ridiculous for the Facebooks of the world to claim they've "solved the dopamine system" or something of the like, but the idea that the networks aren't shaping their users' minds (on the margin) seems so obvious to me that I almost feel like the burden of proof is on someone claiming that they don't do this.

That said, I feel like the breakdown comes between the difference between being able to control users' minds in the abstract vs being able to influence them on certain ideas. I do not think the Zuck army can influence me to be something I'm not, but I'd be surprised if they didn't have the ability to push me in certain directions on certain axes.

As example, my dad is a Fox News diehard - spending time at his house means hearing Tucker et al at all hours of the day, and I find that spending 2-3 days around there starts to do interesting things to me. I don't believe the nonsense they often spew, but I can sense myself becoming gradually sympathetic to certain ideas, or agreeing with certain framings of things.

Abstracting this to more subtle changes in ideology and longer periods of exposure (as I'm sure you know, people use FB a _lot_), it's hard for me to believe that people can't be pushed. Whether or not this is being done, or whether it's profitable or anything remains an open question to me, but IMO the answer of "could TikTok influence certain thoughts (I imagine all of us are more suggestible on certain topics) of someone who watches it for 3 hours a day" is a resounding yes.

Thinking of things this way, I guess my condensed response would be something like "ABC/NBC/CBS could certainly claim to influence the zeitgeist (or could've 20 years ago) but could not influence me to like them more than the internet because that's out of their axis of influencability", which I think is maybe somewhat congruous with what you're saying but not entirely.