Convention and Neurosis Revisited

Hell is people who think hell is other people; hatred is generally ignorance; and other conclusions from one of my favorite passages of all time.

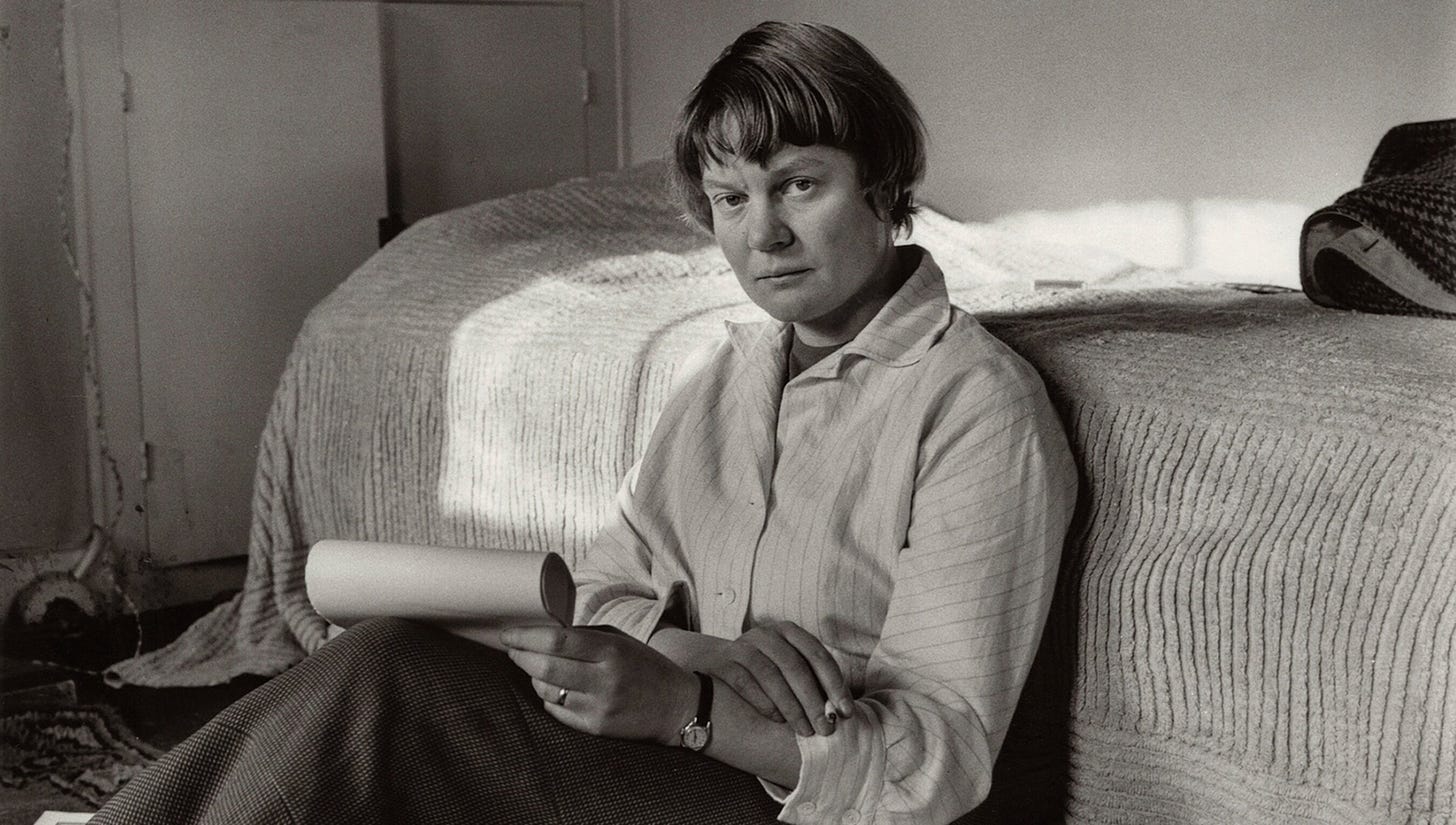

One of the most remarkable moments of my intellectual life came when reading Iris Murdoch’s essay “The Sublime and the Beautiful Revisited.” Right at the start, before even getting into her main argument, she breezily dismisses the two dominant Western philosophies of the mid-20th century. To do so, she uses the following terms to refer to the models of humanity they posit or reflect:

“Ordinary Language Man” is the human being described or implied by so-called ordinary language philosophy. This school, in various forms, rejected philosophical preoccupations with abstractions in favor of quasi-anthropological descriptivism. That is: the question “what is truth” is invalid to ordinary language philosophers; “truth” is whatever people mean when they say “this is the truth,” nothing more and nothing less. Importantly, this means that communities and contexts are what arbitrate philosophical questions; in one community, truth is whatever is written in a given book, while in another truth is whatever this or that authority or institution says, and both of those are roughly full accounts of “what truth is” for the purposes of philosophy. There is little or nothing beyond community conventions. Thus: Ordinary Language man is someone who exists within unproblematized if not unexamined local contexts, someone embedded in and largely satisfied with traditional frameworks of meaning and being. “There’s no mystery here, you’re just using words incorrectly; quit being a weirdo,” such a person might say.

“Totalitarian Man” is the human described by existentialists, whose philosophical preoccupations summed to a kind of solipsism: other people —who are “hell” for Sartre— and their communities and works are unfortunate obstacles to a process of inner realization for the individual, a kind of purification ritual producing a unified will and conscience of whatever arbitrary form.1 While they agree with ordinary language philosophers that there are no transcendent or essential meanings to be found, they reject the patchwork of conventions that structure language and life, and encourage instead the development of a gloomy, myth-like variety of self-knowledge, via a process that seems like a bit of a “Weirdo’s Journey” through e.g. nausea at the “raw facticity” of existence into some state “on the other side of despair” that’s usually under-specified and is, in any event, totally unique to each of us. “There’s only your inner world; words and concepts and people and communities don’t matter; you should be way weirder,” such a person might say.

Writing in 1959, Murdoch was early to see the incompleteness of these models, and in words that seemed to elegantly compress thousands of pages of discourse without any information loss, she explained the proof of their poverty:

“One might say that whereas Ordinary Language Man represents the surrender to convention, the Totalitarian Man of Sartre represents the surrender to neurosis: convention and neurosis, the two enemies of understanding, one might say the enemies of love; and how difficult it is in the modern world to escape from one without invoking the help of the other.

I think about this sentence very, very often; it might be one of the most important things I’ve ever read. Its basic claims easily summarize the psychological and social reality of those schools, but beyond my interest in relitigating past philosophical disputes, I find it much more generally descriptive of intellectual and cultural phenomena in our civilization than might initially be obvious:

we seek escape from convention through neurosis;

we seek escape from neurosis through convention;

both are “enemies of understanding”;

both are “enemies of love”;

“understanding” and “love” are at least related;

something about “the modern world” makes it hard to escape without overcorrection.

All of these points seem both true and profound to me, and not merely “analytically”: as a child of the 20th century, I lived these maneuvers, and I have felt the lack of understanding and of love in my positions again and again. My youth was above all an intense immersion in and elaboration of neurosis contra convention all around me; and I understood and I loved very little. Instead, I judged and hated a great deal. Judgment can feel like understanding, of course, and indeed I think is mostly used for that precise purpose: as a substitute for an understanding we cannot achieve or which we actively resist. And hatred can feel like love: hatred of an other in defense of oneself and one’s community feels not only virtuous but enlivening and ennobling in much the way love can. It provides an object outside of the self, like love, and it quickens the pulse, like love. But at best, judgment and hatred are dead ends: intellectually, emotionally, spiritually, culturally, artistically, they lead nowhere. And at worst, they are part and parcel of the worst evils we perpetrate.

It is not surprising that convention and neurosis are so opposed: what is non-conventional is often relatively considered neurotic, and what fails to be novel and unique (i.e. neurotic to some frames) is usually criticized as conventional (or: conformist, conservative, etc.). It is also not surprising to me that the modern world makes it hard to escape one without the other; I partly blame reactive extremification brought about by scaled telecommunications technologies for this tendency to think and live like dialectician automata optimizing mostly for “group affinity.”

What was and remains shocking to me —and what’s emblematic of what made Murdoch special— was her casual suggestion that understanding and love are related. I believe that Murdoch comes in part to this point of view through her work as a novelist; indeed, Sartre’s incompetence with novels was an early sign to her that his thought was off the mark.

“[His] inability to write a great novel is a tragic symptom of a situation which afflicts us all. We know that the real lesson to be taught is that the human person is precious and unique; but we seem unable to set it forth except in terms of ideology and abstraction.”

If “the real lesson to be taught” cannot be expressed in philosophy “except in terms of ideology and abstraction,” how can it be expressed? And how does Murdoch know that “the real lesson to be taught is that the human person is precious and unique”?2 In both cases, I believe her answer would be: literature (and, more broadly, the arts). Literature teaches us to see others not as symbols —which can be valued or devalued— but as irreducible individuals, “precious and unique”; and literature is how we “teach” others to see this way, too, or at least, how she chose to.

Literature accomplishes this by improving one’s ability to imagine the inner lives of others; imagining the inner lives of others fully —or as fully as one can— brings one close to understanding, and also, strangely, to love. The mystery of the antihero is no mystery at all in this view: in literature, we do not love on the basis of good and evil but of “understood” or “not understood.”3 The tendency of the arts to sidestep systems of philosophy or morality entirely comes first from their grounding in subjective experiences of the world —which always escape such systems— and second from our identification with the subjective experiences of others (that is: the people in e.g. a movie). This is the understanding and love missing from the worlds of Ordinary Language Man and Totalitarian Man, the understanding-thus-love. It is present in a great deal of art, as well as in daily life, so its absence from the models of humanity asserted by the most popular philosophies of the day was noteworthy, if detectable at first only to Murdoch.

In any event: I don’t want to exaggerate. Literature and the arts can teach these things, but they do not necessarily; other things can surely teach them too; and understanding is always, always limited. Murdoch insists on this last point elsewhere in her writing. Nevertheless, and for whatever perhaps personal reasons, I accepted her position as not only obviously correct, but indeed as a kind of vital guidance. It reminded me of Thich Nhat Hanh’s famous assertion:

You cannot resist loving another person when you really understand him or her.

These remarks, among others, are like guardrails for my reactive, critical mind and have driven me to valuable self-skepticism often; my natural tendency is to imagine that I know much more than I do, and identifying the state of real knowledge with love has helped me avert countless disasters in which I might have acted out of partial or projected “knowledge” (sometimes wholly false) and done real damage, usually through anger. And I think that they each also explain much of our shared cultural life, from phenomena like the antihero to the endless see-sawing of societies oscillating between convention and neurosis, while scattered individuals anxiously hope to preserve understanding and love amidst all the sour, scouring invective of Ordinary and Totalitarian Men.

Apart from criticisms of “bad faith” in beliefs or actions, existentialists were very much beyond good and evil. This is a part of why she calls this human type “Totalitarian Man”: to work out the will of the self over and indifferent to your fellow humans, to see people as mere elements of one’s own struggle towards an integrated, fearless utopia “on the other side of despair,” is a basis for one psychology of totalitarianism; it is not the only one, I don’t think. It’s also why there’s such a connection between existentialism, loosely defined (as a cultural vibe more than a specific set of claims), and artistic works involving transgression and violence. The existential hero might kill herself, or she might kill others. In any event, the truth of the matter is that Sarte was wrong; true hell is people who think hell is other people.

A third question: why is it bad that it can only be expressed in ideology and abstraction? As ever, I would argue that ideology and abstraction suffer the same problem as scale does when they intersect with human concerns: they *must* erase particularities, reduce individuals to fungible symbols, compress differences and idiosyncrasies, and thus whatever their output, we do not find ourselves in it. In philosophy, this means: dead theories. In politics, this can mean: dead bodies.

Indeed, I now wish I could rewrite that review of The Sellout, because I’d like to say: I understood how the combination of influences he faced, and how he processed them, led Bonbon to be Bonbon; and it made me sort of love him, even as I recoiled from him.

Love this. You used that Iris Murdoch quote in another post and it sent me into a state over how too much unconventional digging into personhood leads to neurosis. But it also reminds me of Lionel Trilling: “The poet is in command of his fantasy, while it is exactly the mark of the neurotic that he is possessed by his fantasy.”

Along those lines, I think what’s missing in this exploration of convention vs. neurosis is the crucial difference between thought and feeling. When you talk about the “gloomy, myth-like variety of self-knowledge” (big fan!) that leads to some state “on the other side of despair” (so starchily intellectual of these starchy intellectuals not to just call it what it is: joy), what’s missing is the crucial difference between thinking your way into this “other side of despair” vs. arriving and feeling the joy (and love and understanding) there.

The point of rejecting convention and sometimes turning away from at least *the conventions* of community is to reach this place beyond despair that’s described by countless of these unconventional thinkers not as a neurotic destination but the very opposite of that, a place of understanding and love and connection to other humans. I think the crucial distinction here is that the unconventional path certainly leads through the brambles of neuroticism, and that can make you more neurotic, just to put it in simple human terms. But the task at hand is to keep cutting through the brambles until you can FEEL that place beyond despair, where an understanding that the moralism and rules of Ordinary Language Man are hopelessly inadequate, in the face of the higher sensation of understanding, peace, and acceptance that comes from celebrating your own unique, natural, and yes, sometimes gloomy gifts as a human animal. It’s a place beyond thought and judgment and hatred, but as long as you’re neurotically (and might I add CONVENTIONALLY telling yourself, using ordinary language) I NEED TO BE LESS ME AND MORE FULL OF LOVE AND UNDERSTANDING! then you’re just stuck on the brambly neurotic path. You caN FEEL your way off that path, and into a more joyful, loving, understanding state. Thinking your way is harder and slower and when it doesn’t work, it kicks up shame and self-hatred, i.e. I DID THIS BEFORE WHY CAN’T I DO IT NOW?

The answer is to become a poet, in command of your fantasy but never possessed by it. You feel as much as you can. When thought makes you gloomy, you think less and feel more, in that squidgy (did you use that word?) place free from judgement. When your fantasy possesses you, you back up and treat it as a route to creating and celebrating (instead of indulging the illusion that your whole life could become one beautiful sunset orgy of light and sound, which is also the illusion our commercial culture upholds and reinforces, an illusion that makes human animals deeply self-hating and neurotic because they can never reach that imagined nirvana).

Too many words here! LORD, BLESS THIS MESS! <- see how Ordinary Language Man has a lot of conventional paths away from neuroticism? He’s always inserting himself into shit and saying “Stop thinking so much and LIVE LAUGH LOVE motherfuckers!”

In some ways, that understanding of peace is what binds Ordinary Language Man to Totalitarian Man. Ultimately, in spite of appearances, they’re *both* trying to let go of thought and feel more joy. But sadly, they only recognize thinkers who are MEN so the wisdom of the most brilliant human animals in their midst is lost to them forever and ever. lol

Dang it Mills this is very good.

It’s almost so good that I don’t want to sully it with a nominative determinism joke about how Iris is so perceptive. Almost.