Why do you want to write about your mother?

I’m not sure that I do. I’m shocked at this fact: I am not nearly so squared to my mother in death as I was to my father. I don’t think it would surprise anyone who knew us, but I had always imagined that despite it all, my mother was alive in me in the deepest places and thus intelligible to me in ways my father was not. The course of my life took me physically and mentally and psychologically and culturally away from her and towards him, but it seemed to me that this motion affected mostly my “upper” or “outer” self. If nothing else, that like her I am described by medical literature as “having bipolar disorder” suggested to me that we shared a structure or metabolism. And we do. And perhaps that’s why it’s difficult for me to write about her.

What is difficult about it?

Oh, the usual: “words fail.” I cannot “do her justice.” That my father’s soul was hidden seemed very natural; he hid it, and his decision to hide it and keep it hidden was, for him, an act of deliberate and thoughtful will; he believed I think that this was what he should do, and it was in any event what he wanted to do. Thus not being able to describe him beyond his interests, behaviors, mannerisms not only didn’t make a portrait “incomplete” but came to a sort of respect. My mother did not try to hide her soul; she constantly expressed it, in everything, but her soul itself was not fixed; whatever is wrong with my mother and me, it has the effect of making us multiple, vague when we try to specifically instantiate ourselves, incapable of achieving “coherence” of self, if such a thing can exist. My mother could be reduced only to the scale of climate: you could not call her the sun or the rain or an ice storm or a hurricane, and nothing anyone has calculated or computed would generate accurate predictions about her. I think it’s fair to say that no one ever knew her, which made many want to.

People tried?

I had the sense that nearly everyone she met tried. My mother was attractive in every sense; people “gravitated” towards her, but she had no center mass; it’s not clear where the gravity came from. I have as much capacity to describe her as physicists do black holes, with their irrational “singularities”: I can give name to the infinite draw she had, but that name only represents the failure of my explanatory framework, the limits of my mathematics. Yes: everything hurtled towards her and, passing the event horizon, found her missing from the point, suddenly elsewhere.

But yes, as a boy, I watched men and women try and try and try. A policeman fell in love with her and came by the house so often she had to turn out the lights, not out of anxiety but out of her desire not to hurt his feelings; she’d say “he’s lonely Mills, everyone gets lonely.” At some point, some of these people were powerless not to hate her for it. I also hated her for many years, enough that I was for a time something of a misogynist. But even that wouldn’t take, because my mother wasn’t “a woman,” and other women had little in common with her. My rage was only for her; and no one deserved it less.

But wasn’t she difficult?

Listen: I want to talk about her honestly, or about my feelings about her honestly. I am tempted therefore to enumerate the spectacularly abusive things she did when insane or intoxicated, because it will make you sympathetic to me almost no matter what else I say. If I write “I was for a time something of a misogynist,” I myself find it disgusting; but if I write the things she did to me when I was a boy, few would feel anything but sympathy. But I am sick to death of sympathy, of telling the story such that I am a “good” person. My mother and I share every vice either one of us every had, and I had the luckier path: born nearly four decades after she was, I grew up in a world of psychiatrists and psychologists and after-school-specials assuring that dysfunction and incompetence were just “difference”; I have never once paid a price for being mentally ill, beyond the raw experiences and my own shame; my mother paid steep prices again and again and again. She was not a victim and would loathe to be seen as such; she was a powerful, creative, domineering woman who terrified and entranced; but it was no picnic being as crazy as she was when she was. When I was diagnosed, we were in rural New York; we went to a place called Poet’s Walk and smoked cigarettes —by that time, I had finally graduated to menthols, although I left her Benson and Hedges to her, favoring Newport Ice— and she said: “Mills, if I’d known the way I was was something, was a thing I could pass on, I wouldn’t have had children.” She was apologizing. I told her what I feel now: I’m damned glad to have had the chance to be alive on Earth, and I don’t care how badly it goes or ends. (I mean: get real!). She shook her head. I knew then that it was worse for her than for me.

But what did she do to you?

Oh, to Hell with you! To Hell with me. I am Hell itself: clawing back a prideful self-pity no matter what I do. Oh, mom; I’m sorry I used you as a tool to feel justified in my defects; I’m sorry I blamed you for what we share; you forgave me and I will try to forgive myself, but I will never forget what I am capable of or the damage it did to you. It makes abuse pale in comparison. Anyone can lose their mind; anyone can lose their temper, especially with a child like I was; but it’s a special sickness to play these disgusting moralizing games, to always be on the hunt for ways to feel superior. It’s the sickness. It’s what I’ll fight all my life.

Here’s what she “did to me”: she taught me to love people of absolutely all kinds, and to be present with them. She never said it, but she certainly thought that boredom was a failure of attention and imagination; to be bored is to bore the universe with your smallest self while glory abounds. She taught me to love music, art, architecture, natural and cultivated landscapes, high and low cultures. She loved cars! She had a Ford Taurus SHO that she adored. She loved to drive fast. Sometimes she’d drive so fast my sister would cry; she thought less of my sister for it, one of her cruelties being an explosive contempt for anyone who could not rearrange themselves for the sake of joy. She was horrible to my sister, just horrible. Once, she got a ticket for going 80 on a street in Uptown New Orleans called Henry Clay; this street is purely residential and has a 25 mile-per-hour speed limit. It was a feat of physics and of recklessness. I don’t know that I ever saw her afraid for a single second. She loved danger; she loved turbulence on airplanes and was very disappointed when, in my 30s, I became afraid of flying. She taught me to at least try and be brave, and though I’m not, I would be worse without her influence.

She sounds a bit like a hellion.

She was, but she was also capable of incredible decorum, restraint, and generosity. Once, driving back from dinner, my parents came upon a car accident; a man had driven into a tree, and the woman in the passenger seat had gone through the windshield. My mother wrapped her in her coat while they waited for paramedics; when she came home, the coat was soaked in blood. It was nothing to her. She gave things and money away, and if it’s true that she had not earned the money, it’s also true that she loved to buy things and could have used it. Like me, she was very good in a crisis and very bad on a typical weekday; I believe it was she who introduced me to Walker Percy, even taking me to Covington to see where he lived, and he was well-aware of this reality: “It is easier to survive a category five hurricane than it is to get through an ordinary Wednesday afternoon.” My mother was defeated by Wednesdays.

When hurricanes were predicted to hit New Orleans, she’d take us to Memphis to visit Graceland; she didn’t care for Elvis’ music, but she loved Graceland. Men with bad taste delighted her. She was fond of an ostentatious local businessman named Al Copeland, the founder of Popeye’s Fried Chicken, which she and my father loved as well. We’d go to Popeye’s on the way to the beach in Mississippi; I’d scrape my knees on their pumice-stone walls, which made for easy climbing, and she’d talk about seeing Al drive around the horrible New Orleans streets in his fly-yellow Lamborghinis. She found it ludicrous, but it charmed her. She found Popes wonderful, too, although I don’t mean to imply that this is the same. But her attitude towards them was the same: she liked when people achieved difference.

For music, she favored Led Zeppelin, AC/DC, Motley Crue, Def Leppard, Aerosmith, and Pink Floyd (but not the mopey self-obsession of Roger Waters). She also introduced me to Paul Simon; when I was a boy, she sang “Loves Me Like a Rock” to me. She wasn’t musical; she was seeking ecstasy, she was seeking to be “outside herself” through the intensity of music. I know this drive very well; a psychiatrist discouraged it, and was correct to do so; I’m very careful about trying to get outside myself now. My mother and I wanted to escape the void, but that way lies much worse. I wish she’d been able to relax about the void; it’s no great shakes, being empty; everyone might be, and even if they’re not and it’s just us: so what? One of my favorite lines in the parody film Spinal Tap is one I find moving even though it’s presented for laughs: “I’m just as God made me.” Mom knew herself, and could not believe she was “as God made her.” Pride, idealism, the high-standards of a class striver from a somewhat trashy family: she was ashamed not to be more, even as she was more than most people ask to be. Both of us required constant readjustment and reinterpretation; I still do.

What means did she use?

Well, her father had been an orphan and found his metaphysical purchase in the United States Army; he served in World War II, was shot by an Italian, and after recovering stayed in Europe to work in various capacities for the burgeoning American Empire. Mom grew up in Germany, then Italy, then Spain, and because her own mother had no interest in children, was largely raised by nuns. Her first line of reinterpretation, then, was Catholicism. She never stopped being fond of the nuns or of the faith, but at some point it perhaps stopped being a “live hypothesis,” so to speak; she and my father got into Transcendental Meditation, and she felt she’d seen real evidence of the divine; it didn’t seem to matter as much as I’d have thought, though. She moved through phases: she read novels and then stopped; she became a mother and then lost interest; she became a calligrapher and then grew bored; she was social and then grew sick of her friends. I assume she experienced these things as broken-heartedness. She had a terrible habit of turning on people; she cut people off, had “fallings out,” dropped connections. It was evident when she died that many bore those wounds for decades; they’d reach out: “I’m sorry about your mother…” and then would tell me that it had been very difficult when she left their lives, that she had said cutting things to them they still recalled. I know how they feel, and I know how she felt too. My mother and I always found it easy to believe that we’d been mistreated, that others hated us, that others were the abusive ones, so we were always able to mistreat, hate, and abuse.

How did she die?

My God, she really did it her way. I suppose it sounds awful, but it was also very fitting. My father shot himself in the head in 2021, while she was walking the dog; she knew he was planning on it, they had discussed it, and she was glad he did it while she was out. She said that he looked peaceful and relieved when she found him. There was, mercifully, no exit wound. The police took the gun and his suicide note and lost the note, but I know what was in it, roughly, and the New Orleans Police Department has a lot on their plate (and have historically been messy eaters).

My mother was surprised at the effect this had on her. To tell the story of their marriage would be impossible. They lost two children: one to anencephaly, one to a late miscarriage. My father was a good husband in some senses, extraordinary in fact; in others, he was an awful husband; the same can be said of her as a wife, and probably of everyone in a marriage, but the particulars in their case meant that they were not “close” in the way you’d expect would lead to pronounced mourning. They separated for more than ten years, although dad visited most mornings and we continued vacationing together, and neither dated anyone else; when Katrina destroyed his house and most of what he had in it, they evacuated together and then simply resumed living together afterward in our old family home, a house she loathed. Little was provided in the way of explanation, but they fit together fine and didn’t fight. But they didn’t seem “in love,” not at all.

Indeed it wasn’t clear that what she experienced was mourning. She reflected often after he died that she found it all surprising, this last chapter: “You know, for our entire marriage, your father was something of an asshole, and I was quite social and fond of people; and in the last 15 years, he became a very sweet man, and I turned into a horrible bitch!” It amused her, but pained her too. What had the rows been about, if not their essences, their moral values? What did it mean if it could all invert like that? (It’s a profitable thing to reflect on, I think).

After he died, she was unmoored; her schedule began to change, her drinking —she was, apart from a few stretches of several years, a lifelong alcoholic— grew worse, and eventually she had a stroke which robbed her of her hearing. Unable to converse with strangers, or anyone really, she lost the will to live. She could no longer get out of herself. She watched a lot of television; she abandoned the sorts of projects which once sustained her, unable to believe in her flights of fancy any longer. She was full of anger, and hated it about herself. She wasn’t a present grandmother, and hated it about herself.

I think the shortest way to put this is: when it became impossible for her to will herself into the form she wanted, when she could no longer get out of herself socially or in any other way, it became torture for her to live. Nothing reached her deeply. Nothing pulled her mind into a future, and the past was drained of meaning, was cloudy anyway.

She told me she, too, was going to kill herself. As I did with my father, I talked with her about it a lot. In such a circumstance, I could think of nothing to do but cover various corners. I told her that I loved her and believed she could have another ten very good years if she got herself together, sobered up, perhaps moved in with us; she told me she disagreed, and while I was emphatic, I applied no pressure; she understood I wanted to her live and thought she could do so well, but I don’t think I ever persuaded either one of them of anything in particular: strong “personalities,” strong pride.

She caught a cold and told me: “I’m not going to treat this. It’ll turn into an infection and I’ll let that kill me.” I told her that this seemed an especially awful way to go, but again: she had her own way. She printed out psychotic-looking homemade DNRs and put them everywhere, but she fell down outside the house and a neighbor took her to the ER; she was furious to wake to find she’d been given antibiotics, but the plan was kaput.

Back home, she told me her new plan: to starve herself to death. I thought this was also quite a bad plan, but I couldn’t deny that it expressed a few themes of her life; she’d had profoundly disordered eating for much of her life and was certainly capable of it, and starvation was a physicalized expression of her will to disappear par excellence. No act, no drug, no event: a private return to dust. She said she wanted no hospice and no visitors: “No fucking vigils. No candles. I don’t want anyone in here but you and your sister.” I told her that after she lost consciousness I’d have to call hospice, unless she wanted me to bathe and change her, and she acquiesced. I was surprised to learn from the (wonderful) hospice nurse that this isn’t uncommon; she said about half of their patients have no medical complaint. I imagine people don’t like to talk about this.

After a week or so, she became corpse-like, waxy; she only moaned, her eyes wild and her remaining muscles seeming to tense painfully; I’d touch her hand and she’d seem to want to speak, but only moans came. I suppose it was hard to be her son then; I didn’t think about how it felt for me at the time and now I can’t really remember anything beyond the visual and practical details. She slipped further and further away, and one day, she died. I wouldn’t call it peaceful, but it was what she wanted and she got it. I took down the DNRs and saintly neighbors and friends helped clean up. They cremated her body and it sits on my shelf as I write, next to a lock of my father’s hair, in an urn she’d not have liked. I wrote the obituary and prepared myself for the changes to come, and come they have.

I have filled my room with photos of both of them, which seem like portals to ultimate mystery to me. Where are they? Where did they go? Did anyone ever know them? What were they? Were they ever here? Could I have done more? Could we —the living, their relatives, anyone— have been enough to hold them happily in this vale of tears? But this is all nothing: “the manner die[d] with the matter.” The puzzle of their selfhoods has been solved. Memento mori.

Don’t you feel angry at her?

Oh, sure; I can think about whatever I want, can’t I? I can think: you fools, you old fools, how could you stumble at such a low hurdle? To lose yourself to addictions as they did after lifetimes of learning about addictions, after having their own lives upended and marred by the addictions of others, isn’t that awful? I could make great hay of the tragedy; her stroke occurred after a vaccination! I could operate a profitable publication blaming whomever and whatever is available; I could set up shop as someone wronged by fate, by the state, by the distillers, by the makers and prescribers of benzodiazepines. But please: death is what happens, and it would be vulgar and degrading —this is her, speaking through me, this high-hat, high-handed style— to even breathe the name of some government agency while talking of her and how I loved her and how I miss her. They were both in their mid-70s. As they both loved to say: “If it’s not one thing, it’s another.” Indexing on details is a path to misery, I think. The end had to come; the end came; it was gruesome because of what we are, and yet I feel real guilt at how much easier it was for me than it will be for most everyone, indeed almost certainly for you —you!— reading this. We had every conversation; I told them everything I wanted to, and they told me what they seemed to want to, too; there was no sudden absence, no sense of regret; they each pardoned me and I pardoned them. Neither of them ever lingered anywhere they didn’t want to be anyway —boy, did they get out of scenes quickly— and they didn’t linger at the end, either.

In any event: anger hurt my mother more than anything else, her own anger; I will not recapitulate her spiritual ruin any more than is mandated by Heaven and my genes (nor will I strain to avoid it, for ruin is what I was born for). Yes: I wish it had been different. I think they were beautiful people with beautiful souls, all torn up but shining despite that, and I would have liked for my children to know them. They each felt there was nothing left to know, and to gainsay the elderly from middle age is not different than to gainsay the hormonal nightmare of adolescence from the idyll of early childhood. I don’t want to be a five-year old telling a 15-year old that “I’ll never catch cooties.”

What do you think she thought of you?

I don’t know. I know she was proud of me, but often for things that were in themselves not that important to her. She liked that I’m quick; she liked that I have interests. She was uncomfortable with how weird I am; she mentioned it in disgust a handful of times, and I think I understand why. God, psychiatrists told me she was “an abusive narcissist.” Let me tell you a sequence and you tell me how useful such concepts are:

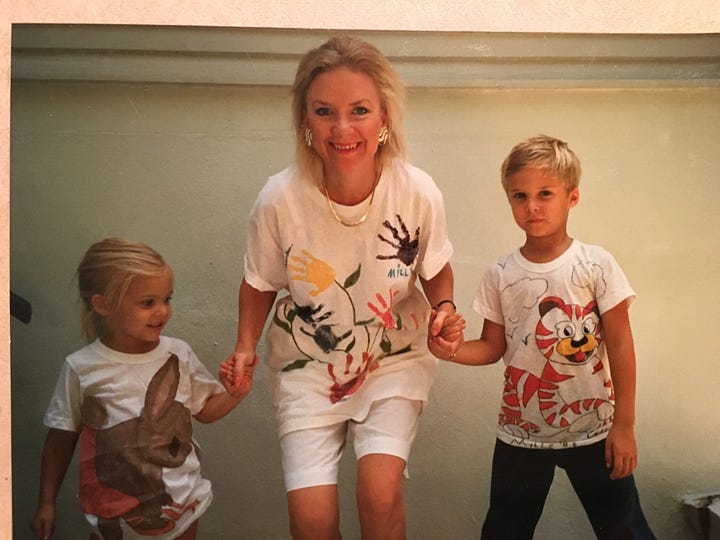

She led to me to Paul Simon; when I loved Paul Simon, she bought be Paul Simon cassettes and played them in the car endlessly. When Rhythm of the Saints came out, I became rapidly monomaniacal about percussion, thanks to Olodum’s work on “The Obvious Child.” She’d play it as often as I wanted and she loved it with me.

I took old paint cans and buckets and made myself a drum set, trying to imitate Olodum and Steve Gadd both. Once, I dropped a can of outdoor paint on the floor, ruining a rug; she told me it was perfectly all right, and helped me recompose myself and clean up, and told me to keep at it.

After a year or two, she bought me a used drum set; to do so, she had to schlep around to pawn shops and music stores, and she did. She brought it home and destroyed her own home’s atmosphere in so doing: for the rest of my life there, I played drums —very loud, shaking the light fixtures, getting the police called on me, having friends with amplified instruments over to “jam,” horribly— for hours and hours every day. She —often hungover— celebrated it! She adored it!

This narcissist supported me so automatically and deeply very often, and I heaped abuse and contempt on her for her drinking, drinking which may have ameliorated (before, of course, increasing) her suffering: her sorrow over not being what she’d dreamed of, over the lost sons, over the difficult marriage, over her father’s early death, over her own mother’s quite-severe abuse, over being involuntarily committed for six months when I was eight years old (after developing paranoid delusions and stalking and harassing district attorneys around the Gulf South, some of whom didn’t take it in stride). God! The way we reduce one another for our own purposes! “It’s healthier for you to hate her, Mills,” a wonderful doctor said; “you should think of what you might be if she hadn’t done the things she did.” Should I? Well, what would I be if I could fly, or were immortal, or were twice as talented, or half as lazy? Why should I torture myself and others with these counterfactuals, when my mother —she of pounding headaches— let me pound 7/4 exercises and paradiddles for hours after school? Why should I not focus on the things she was able to do for me?

Would she like this post?

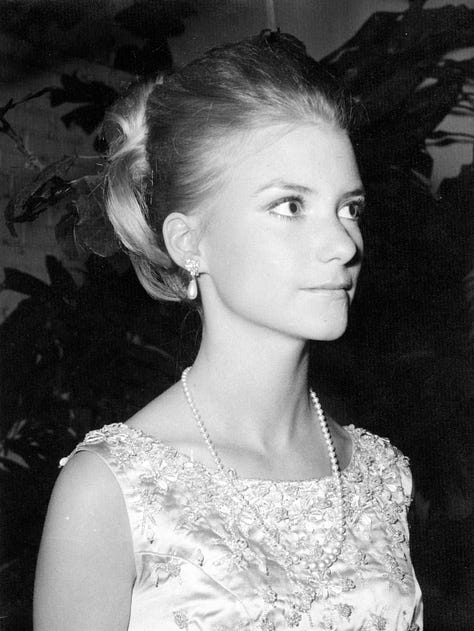

She would like that I wrote it, but she’d find all this a bit treacly, and she’d surely quibble with some details. She was always reinventing herself, and she didn’t recognize earlier iterations at all; she didn’t have a reliable memory for herself, although she did for other things, especially languages. She liked that I existed; she couldn’t in the end be reached by me or anyone, lost in herself and all alone, but she approved of me overall, although by the end, to protect myself, I had to be a bit formal with her, and I think she felt it. I think of her now as a solitary young girl, beaming, unaware that she’d wind up alone no matter what she did: no matter how beautiful she was, or charming, or talented. Despite all the arts, all the friends, all the glittering evenings “living well” in New Orleans and afterward, she wound up alone in herself and not able to love herself, not able to feel the love of others: rabidly pushing others away, thrashing and crashing.

I could write forever about her works: her needlepoint, her decorated Muses shoes, her calligraphy, and so on. I cannot write about how my early childhood felt without ruining my mood; when we were merged, in the true union of childhood, it was the most beautiful time, and I think for her especially. And then that, like everything, went away. She knew I remembered it, I hope; I tried to tell her. I have a sense of what Heaven might feel like, I think; it does not make me feel worse about life on Earth. She would’ve been disappointed if it did, and even now, I don’t want to disappoint her, or dad; and I’m glad I don’t; their occasionally hard expectations led to the only good things about me.

Beautiful and fitting homage in a way only you can accomplish.

This feels like an awful thing to say but I wish you could get into my head and explain my life to me in a similar way. You have a way of *seeing* that I just can't access. And the words to express what you see in a way I just don't have. I think that's what makes this a beautiful post--you saw your mother in a way that few (any?) can, and you're able to give us a glimpse into that view in words.

And it makes me reflective! What else don't I see? I really wonder.

Anyway, thank you for writing this. God rest your mother, and God bless you and yours.

❣️